Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is an autoimmune disease in which the immune system mistakenly destroys the insulin-producing cells (beta cells) in the pancreas. Insulin is an essential hormone that regulates the amount of glucose in the blood. Because people with T1D can no longer produce insulin, they must continuously monitor their blood glucose and take insulin with every meal to survive.

The “Dark Ages” of Diabetes Treatment

As if managing Type 1 diabetes isn’t challenging enough with constant glucose checks, carb counting, and insulin dosing, imagine if you were living with T1D 75 years ago, prior to the availability of the medical advancements we have today. You would sterilize your needles and large glass syringes by boiling them daily. Sharpen your needles manually using an abrasive stone. Test your urine for excess sugar by heating it in a test tube mixed with a chemical solution. And your blood glucose would only be checked in a doctor’s office once a month! The complications you would inevitably develop from diabetes would be viewed as “normal” and nothing could be done to slow their progression. This is during a time in which the medical community thought it was nearly impossible to regulate a diabetic’s blood sugar. I guess if I was only checking my blood glucose once a month, I’d believe this, too.

Advancements in T1D Care

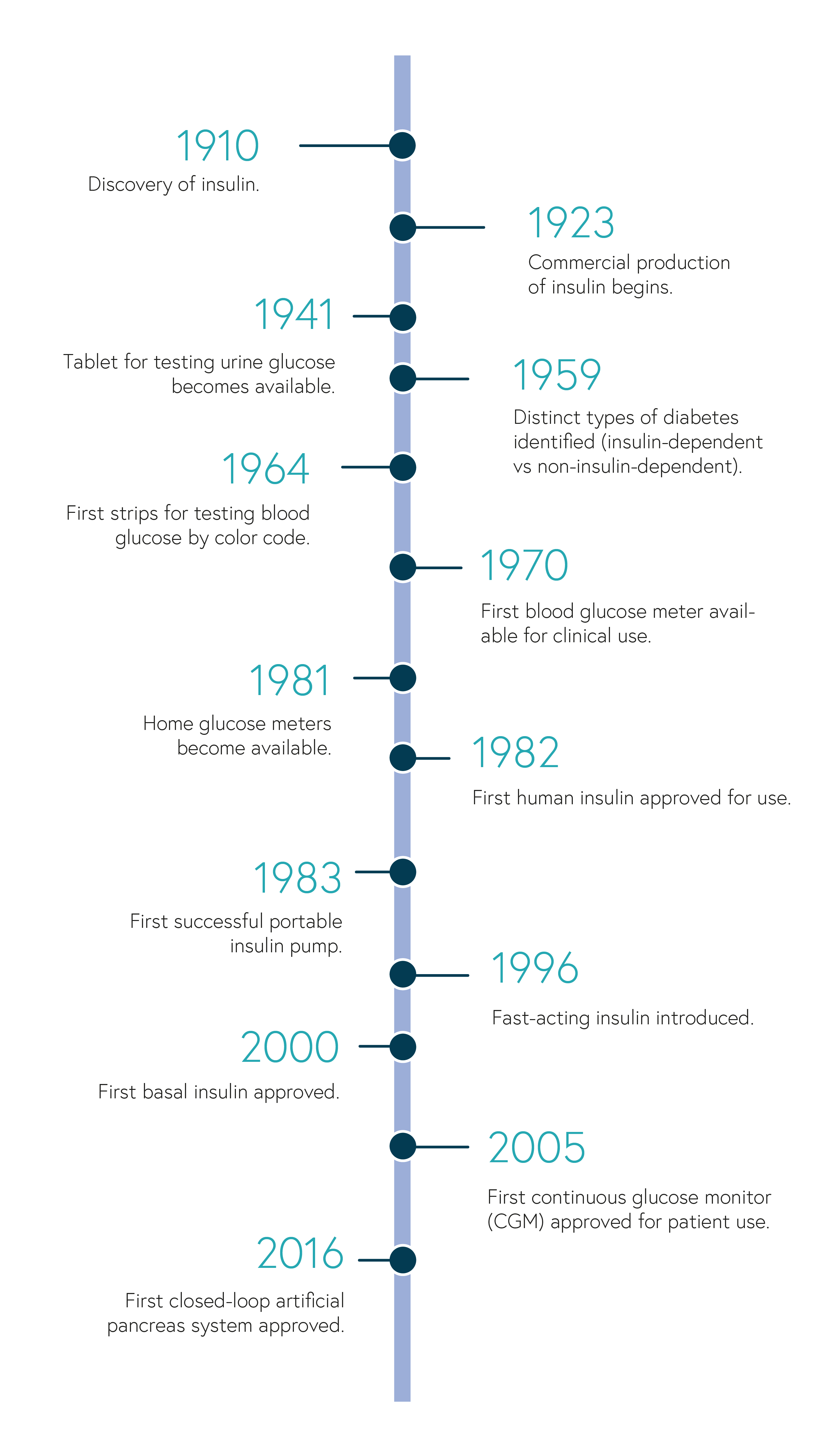

Treatments and technological tools for managing T1D have come a long way in the last 100+ years since the discovery of insulin. This timeline highlights a few of these milestones.

(based on the American Diabetes Association 75th anniversary timeline)

Today, we have disposable syringes, insulin pens, continuous glucose monitors, insulin pumps, and glucose meters, to name a few, and some of which we may take for granted. These tools help people to better regulate their blood glucose and optimize insulin dosing, improving overall quality of life and decreasing the risk for complications. Although scientists still don’t fully understand what triggers the immune system to destroy the insulin-producing beta cells, research is developing rapidly with the goal of achieving blood glucose control while lessening the burden of diabetes management. The artificial pancreas, pancreatic islet transplantation, beta cell regeneration, and smart insulin are only a few of the many exciting advancements that may revolutionize T1D treatment.

- Artificial pancreas (closed-loop system). In 2016, the FDA approved the first closed-loop insulin delivery system, a new technology that connects a CGM with an insulin pump to automatically monitor glucose levels and adjust insulin delivery. A computer-based algorithm receives glucose readings from the CGM, determines the dose of insulin needed, and sends instructions to the pump to release that amount of insulin. The goal of this system is to mimic the function of a healthy pancreas by regulating blood glucose and reducing the occurrence of hypoglycemia (extremely low blood sugar).

- Pancreatic islet (beta cell) transplantation. Islets are clusters of cells in the pancreas that contain insulin-producing beta cells. Healthy beta cells from the pancreas of a deceased donor are injected into a particular vein of the patient with the goal of reducing, or even eliminating, the need for insulin injections. This procedure is limited to certain patients due to the shortage of donor cells and risks associated with transplants. Each procedure injects 400,000 islets, and more than one injection is needed to eliminate the need for insulin injections. As with most transplants, the patient would also need to take drugs to suppress the immune system so that it doesn’t destroy the donor cells. Immune suppression is associated with an increased risk for infection and cancer. Physicians would have to weigh the benefits with the risks when deciding if a patient is eligible for this procedure.

- Beta cell regeneration. Regenerating, or restoring, beta cells in the pancreas would eliminate the need for donor cells. This procedure uses a naturally-occurring growth factor to stimulate progenitor cells—a special kind of cell that can turn into different kinds of cells—in the pancreas to produce more beta cells. Because the immune system in people with T1D attack beta cells, researchers are looking for ways to avoid immune destruction of these newly formed insulin-producing cells without the use of immunosuppressive drugs.

- Smart insulin. Smart insulin, or glucose-responsive insulin is designed to automatically activate or deactivate in response to the levels of glucose in the blood. It would circulate throughout the body, and only activate when blood glucose levels are high. After the amount of blood glucose is lowered, the insulin would deactivate. The smart insulin patch is thin, silicon patch with more than 100 microneedles containing glucose-responsive insulin. Research is still in the early stages, but it is the hope that smart insulin will promote tighter glucose control and lower the risk for hypoglycemia.

With all the promising research taking place, management of T1D can only continue to improve. Perhaps not too long from now, diabetes-related complications and reduced life expectancy will become a worry of the past. For now, I look forward to the day when my daughter and I can indulge in a brownie-bottom sundae without agonizing over carb count and high blood glucose numbers.